http://www.instructables.com/id/Build-Lifesize-Space-Marine-Armor-in-352-Terribly-/?ALLSTEPS

Category: Uncategorized

http://www.instructables.com/id/From-3d-printed-part-to-metal-the-lost-plaabs-me/?ALLSTEPS

“Impatience asks for the impossible, wants to reach the goal without the means of getting there.”

I frequently lament a particularly prevalent pathology of our time — our extreme impatience with the dynamic process of attaining knowledge and transmuting it into wisdom. We want to have the knowledge, as if it were a static object, but we don’t want to do the work of claiming it — and so we reach for simulacra that compress complex ideas into listicles and two-minute animated explainers.

Two centuries before our era of informational impatience, the great German idealist philosopherGeorg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (August 27, 1770–November 14, 1831), who influenced such fertile minds as Nietzsche and Simone de Beauvoir, addressed the elements of this pathology in a section of his masterwork The Phenomenology of Mind (public library).

Hegel writes:

The goal to be reached is the mind’s insight into what knowing is. Impatience asks for the impossible, wants to reach the goal without the means of getting there. The length of the journey has to be borne with, for every moment is necessary; and again we must halt at every stage, for each is itself a complete individual form, and is fully and finally considered only so far as its determinate character is taken and dealt with as a rounded and concrete whole, or only so far as the whole is looked at in the light of the special and peculiar character which this determination gives it. Because the substance of individual mind, nay, more, because the universal mind at work in the world (Weltgeist), has had the patience to go through these forms in the long stretch of time’s extent, and to take upon itself the prodigious labour of the world’s history, where it bodied forth in each form the entire content of itself, as each is capable of presenting it; and because by nothing less could that all-pervading mind ever manage to become conscious of what itself is — for that reason, the individual mind … cannot expect by less toil to grasp what its own substance contains.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak for Robert Graves’s little-known children’s book. Click image for more.

Our mistaken conception of knowledge as a static object is also the root of our perilous self-righteousness and the tyranny of opinions. (“When you come right down to it,” Borges observed,“opinions are the most superficial things about anyone.”) Knowledge, Hegel argues, isn’t a matter of owning a truth by making it familiar and then asserting its ideal presentation, but quite the opposite — an eternal tango with the unfamiliar:

The form of an ideal presentation … is something familiar to us, something “well-known,’ something which the existent mind has finished and done with, and hence takes no more to do with and no further interest in. While [this] is itself merely the process of the particular mind, of mind which is not comprehending itself, on the other hand, knowledge is directed against this ideal presentation which has hereby arisen, against this “being familiar” and “well-known;” it is an action of universalmind, the concern of thought.

What is “familiarly known” is not properly known, just for the reason that it is “familiar.” When engaged in the process of knowledge, it is the commonest form of self-deception, and a deception of other people as well, to assume something to be familiar, to give assent to it on that very account.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Errol Morris’s magnificent New York Times essay series on the anosognostic’s dilemma, Hegel adds:

Knowledge of that sort, with all its talk, never gets from the spot but has no idea that this is the case. Subject and object, and so on, God, nature, understanding, sensibility, etc., are uncritically presupposed as familiar and something valid, and become fixed points from which to start and to which to return. The process of knowing flits between these secure points, and in consequence goes merely along the surface. Apprehending and proving consist similarly in seeing whether everyone finds what is said corresponding to his idea too, whether it is familiar and seems to him so and so or not.

True understanding, Hegel argues, requires that we demolish the familiar, overcome what psychologists have since termed the “backfire effect,” and cease clinging to the fixed points of our opinions:

The force of Understanding [is] the most astonishing and great of all powers, or rather the absolute power.

[…]

The life of the mind is not one that shuns death, and keeps clear of destruction; it endures death and in death maintains its being. It only wins to its truth when it finds itself utterly torn asunder.

The Phenomenology of Mind remains one of the most mind-stretching treatises ever written. Complement this particular passage with E.F. Schumacher on the art of adaequatio and how we now what we know and Hannah Arendt, who was heavily influenced by Hegel, on the life of the mind.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthlydonation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

—-

Shared via my feedly reader

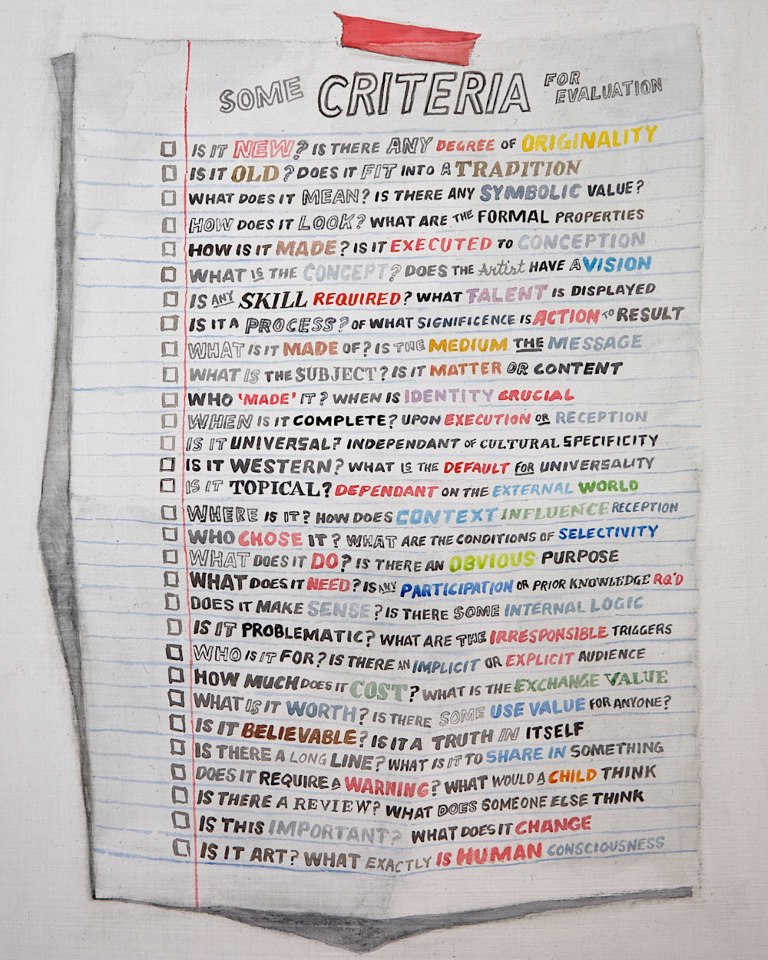

QUESTIONS FOR LOOKING AT ART

Forklift Driver Klaus

SEED

Lori Nix

Spinoza!

memory palace podcast

google art project

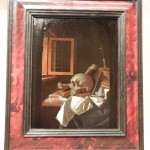

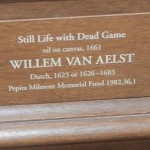

Roland Flexner on vanitas painting

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/06/150610-octopus-mollusk-marine-biology-aquarium-animal-behavior-ngbooktalk/?utm_source=Facebook&utm_medium=Social&utm_content=link_fb20150613news-octopusbooktalk&utm_campaign=Content&sf9914294=1

Blaise Pascal on the Intuitive vs. the Logical Mind and How We Come to Know Truth

// Brain Pickings

“The heart has its reasons, which reason does not know…”

“Your intuition and your intellect should be working together… making love,” Madeleine L’Engle asserted in contemplating how creativity works. Ray Bradbury believed that intuition and emotion should guide creative work, the intellect coming in only to revise after the act of creation, and Susan Sontag admonished against buying into this polarity in the first place: “The kind of thinking that makes a distinction between thought and feeling is just one of those forms of demagogy that causes lots of trouble for people.” But it’s hard to deny that in most minds there exists a combination of the two and in very few a perfect balance.

The duality of these two faculties and their interplay is what the great French physicist, philosopher, inventor, and mathematician Blaise Pascal (June 19, 1623–August 19, 1662) explores in Pensées (free ebook | public library) — the same masterwork of fragmentary reflections that gave us Pascal on the art of changing minds.

In a passage outlining the difference between the intuitive and the mathematical mind — “mathematical” meaning “logical” or “rational” — he writes:

In the intuitive mind the principles are found in common use, and are before the eyes of everybody. One has only to look, and no effort is necessary; it is only a question of good eyesight, but it must be good, for the principles are so subtle and so numerous, that it is almost impossible but that some escape notice. Now the omission of one principle leads to error; thus one must have very clear sight to see all the principles, and in the next place an accurate mind not to draw false deductions from known principles.

All mathematicians would then be intuitive if they had clear sight, for they do not reason incorrectly from principles known to them; and intuitive minds would be mathematical if they could turn their eyes to the principles of mathematics to which they are unused.

Suggesting that it is a greater failure to be unintuitive than to be unanalytical, Pascal adds:

The reason, therefore, that some intuitive minds are not mathematical is that they cannot at all turn their attention to the principles of mathematics. But the reason that mathematicians are not intuitive is that they do not see what is before them, and that, accustomed to the exact and plain principles of mathematics, and not reasoning till they have well inspected and arranged their principles, they are lost in matters of intuition where the principles do not allow of such arrangement. They are scarcely seen; they are felt rather than seen; there is the greatest difficulty in making them felt by those who do not of themselves perceive them. These principles are so fine and so numerous that a very delicate and very clear sense is needed to perceive them, and to judge rightly and justly when they are perceived, without for the most part being able to demonstrate them in order as in mathematics; because the principles are not known to us in the same way, and because it would be an endless matter to undertake it… Mathematicians wish to treat matters of intuition mathematically, and make themselves ridiculous.

Art from ‘The Boy Who Loved Math,’ a children’s book about the life of legendary mathematician Paul Erdos. Click image for more.

But this mathematical (or logical) mind is only a subset of the intellect that stands opposite intuition:

There are then two kinds of intellect: the one able to penetrate acutely and deeply into the conclusions of given premises, and this is the precise intellect; the other able to comprehend a great number of premises without confusing them, and this is the mathematical intellect. The one has force and exactness, the other comprehension. Now the one quality can exist without the other; the intellect can be strong and narrow, and can also be comprehensive and weak.

Pascal argues that our failure to understand the principles of reality is due to both our impatience and a certain lack of moral imagination:

Those who are accustomed to judge by feeling do not understand the process of reasoning, for they would understand at first sight, and are not used to seek for principles. And others, on the contrary, who are accustomed to reason from principles, do not at all understand matters of feeling, seeking principles, and being unable to see at a glance.

He considers what mediates the relationship between our intellect and our intuition:

The understanding and the feelings are moulded by intercourse; the understanding and feelings are corrupted by intercourse. Thus good or bad society improves or corrupts them. It is, then, all-important to know how to choose in order to improve and not to corrupt them; and we cannot make this choice, if they be not already improved and not corrupted. Thus a circle is formed, and those are fortunate who escape it.

Pascal makes a peculiar and rather poignant aside — doubly so in our divisive age of harsh snap-judgments directed at others via soundbites and status updates — suggesting that our inability to appreciate the singular gifts of other people is essentially a failure of our own intelligence, for the prerequisite for appreciation is comprehension:

The greater intellect one has, the more originality one finds in men. Ordinary persons find no difference between men.

One of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s original watercolors for ‘The Little Prince.’ Click image for more.

Three centuries before the most beloved line from the most beloved children’s book — “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly,” wrote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. “What is essential is invisible to the eye.” — Pascal observes:

The heart has its reasons, which reason does not know… We know truth, not only by the reason, but also by the heart.

Nearly four centuries later, Pensées remains a revelatory read, full of timeless wisdom on everything from navigating uncertainty to the key to eloquence. Complement this particular portion with a fascinating read on the role of intuition in scientific discovery, Carl Sagan on the necessary balance between skepticism and openness, and Hannah Arendt on the crucial difference between truth and meaning.

various links

ATEC-FAB UTDallas : Hadi Zadeh – Assignment 8 Waffles

http://atecfabutd.blogspot.

http://beautifuldecay.com/

Laser Kerf bending: http://www.core77.com/posts/