Author: Joe Meiser

ribbon mics

Kim Joon

The Chronicle of Higher Education

March 10, 2014

By Sunil Iyengar and Ayanna Hudson

In public-policy battles over arts education, you might hear that it is closely linked to greater academic achievement, social and civic engagement, and even job success later in life. But what about the economic value of an arts education? Here even the field’s most eloquent champions have been at a loss for words, or rather numbers.

Until now.

In December, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis released preliminary estimates from the nation’s first Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account. The account is meant to trace the relationship of arts and cultural industries, goods, and services to the nation’s ultimate measure of economic growth, its gross domestic product.

The numbers are still a work in progress. In this context, “arts education” refers only to postsecondary fine-arts schools, departments of fine arts and performing arts, and academic performing-arts centers. Yet even for this limited cohort, the findings are impressive:

- The total economic output (gross revenue and expenses) for arts education in 2011, the most recent year for which data are available, was $104-billion. Arts education thus claims the second largest share of output for all U.S. arts and cultural commodities, after the creative services within advertising.

- In 2011, arts education added $7.6-billion to the nation’s GDP.

- In that year alone, arts education as an industry employed 17,900 workers whose salaries and wages totaled $5.9-billion.

- For every dollar consumers spend on arts education, an additional 56 cents is generated elsewhere in the U.S. economy.

Again, these figures do not include design schools, media-arts departments within schools of communications, or creative-writing programs—to name just a few notable omissions from the world of higher education. And yet the results are in line with a series of claims that have fueled arts advocates in recent years. While not grounded in economic theory, those arguments have portrayed arts education as a conduit to greater creativity and innovation in the work force.

It’s not just arts enthusiasts who feel this way. The Partnership for 21st-Century Skills, a coalition of business and education leaders and policy makers, found, for example, that education in dance, theater, music, and the visual arts helps instill the curiosity, creativity, imagination, and capacity for evaluation that are perceived as vital to a productive U.S. work force. And the Conference Board, an international business-research organization, polled employers and school superintendents, finding that creative problem-solving and communications are deemed important by both groups for an innovative work force. Additionally, IBM, in a 2010 report based on face-to-face interviews with more than 1,500 CEOs worldwide, concluded that “creativity trumps other leadership characteristics” in an era of relentless complexity and disruptive change.

While businesses and educators seem to agree on the significance of creativity and innovation to the U.S. economy, the higher-education community is wisely investing more strategically in understanding those ties. The Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities seeks to transform the character of academic research institutions by harnessing “new energy within the arts as well as the infusion of arts and design practices in other disciplines and methods.” Another coalition, the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project, is starting to compile extensive survey data on the financial and career outcomes of people who have received formal arts education, regardless of whether they have pursued arts careers.

Why, then, the paucity of solid economic analyses to inform funding and policy decisions about arts education? First, as we’ve suggested, the data simply were not there. But there could also be another reason.

In 2004, an influential RAND report, “Gifts of the Muse,” distinguished between two classes of benefits that derive from arts participation in general. There are intrinsic benefits, which pertain to “a distinctive type of pleasure and emotional stimulation” for the participant, and there are instrumental benefits, which are “output-oriented” and “quantitative.” Intrinsic benefits are “satisfying in themselves,” while instrumental benefits contribute measurably to the broader public. (Think of the local economic impact from an arts festival, for example, or the social cohesion it engenders.)

According to the authors, one of whom is the economist Arthur C. Brooks, now head of the American Enterprise Institute, art’s instrumental effects were being touted at the expense of its more subtle and inherent traits, whose benefits are harder to quantify and therefore have proved less useful in public-policy arguments. The RAND report urged the arts community to develop more resonant language to capture the value of intrinsic benefits, even though they are essentially personal and subjective.

The time has come to ask: Is this a false duality? In the years since the report’s publication, we have seen arts managers make great strides in deploying audience surveys with sophisticated metrics around how “absorbed” or “captivated” people feel after watching a live performance. But we’ve also seen cognitive neuroscience begin to map the way art works on the brain: the physiological and psychological series of events that occur when someone draws or plays or listens to music. Are these not instrumental techniques for measuring what we previously thought to be ineffable?

If so, then economics is another domain where the barrier between intrinsic and instrumental is fast eroding. It is economists, after all, who preside over some of the world’s leading scientific theories about happiness and the measurement of subjective well-being. What could be more intrinsic than that? In the same way, economic data about arts and arts education can afford us more empirical insights in studying the societal benefits of creativity and innovation.

There may be a turnaround yet. In January, advising an international arts summit in Santiago, Chile, the Georgia State University economist Bruce Seaman began a speech by declaring the old intrinsic-versus-instrumental label useless, since “the only valuation issue worth addressing is which instrumental values to emphasize.”

We anticipate a time when arts education is universally valued, on its own terms, as integral to higher education. Until then, the Bureau of Economic Analysis account can help. The arrival of federally certified statistics on the value of arts education to U.S. economic growth gives arts educators, businesses, policy makers, and the general public a national, reliable measure to underscore at least one kind of instrumental value. For those who question that value in dollars and cents: Bring it on.

Sunil Iyengar is director of research and analysis, and Ayanna Hudson is director of arts education, both at the National Endowment for the Arts.

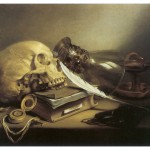

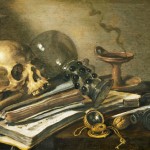

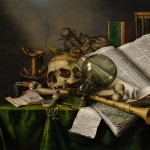

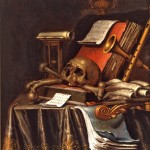

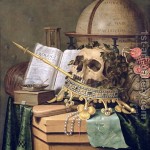

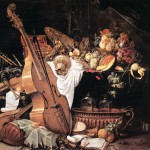

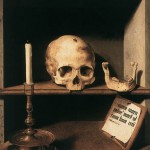

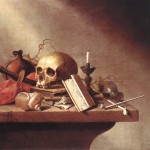

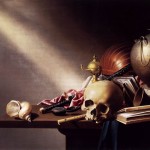

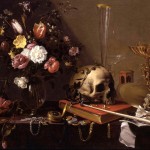

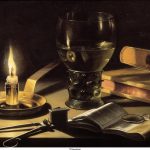

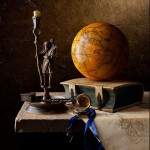

memento mori

cheese plates

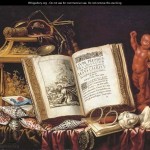

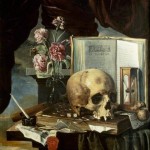

Vanitas paintings

- Heda

- Heda

- Willem Claesz Heda

- Heda

- Allegory of Charles I of England and Henriette of France in a Vanitas Still Life *oil on canvas *146.1 x 120 cm *17th century